Part 3: Plotting with ggplot2

So far we have covered:

- data types in R

- reading in data

- subsetting data

- reading documentation

- using functions

- saving data

- reshaping data

Of course, we haven’t used one of R’s most powerful assets: graphics. This section is dedicated to creating a plot from the data. While R has very powerful default plotting functions, we will be using the “ggplot2” package for three reasons:

- It relies on a consistent “grammar of graphics” that gives a clear relationship between the data and the visualization

- It requires consistently “tidy” data, with one row per observaion

- It’s quite popular with the kids nowadays

We will additionally include a supplementary file for creating plots in the default plotting system for those who are curious.

Expected Outcomes

After this section, you should have the tools to:

- create a simple plot in ggplot2

- save plots

Again, since this is a three hour workshop, we do not expect mastery, but this at least should give you a starting point. With that in mind, let’s get started!

Packages

We will be using the ggplot2 and readr packages, both of which are in the tidyverse.

> library("tidyverse")Loading tidyverse: ggplot2

Loading tidyverse: tibble

Loading tidyverse: tidyr

Loading tidyverse: readr

Loading tidyverse: purrr

Loading tidyverse: dplyrConflicts with tidy packages ----------------------------------------------filter(): dplyr, stats

lag(): dplyr, statsData

We will be using the same data as before, but we will introduce a new function for reading in data from the readr package called read_csv(). This avoids conversion of characters (strings) to factors, provides better error messages, and is generally more efficient.

> fungicide.tidy <- read_csv("data/FungicideTidy.csv")Parsed with column specification:

cols(

Experiment = col_character(),

Julian.Date = col_integer(),

Cultivar = col_character(),

Severity = col_double()

)> fungicide.tidy# A tibble: 54 x 4

Experiment Julian.Date Cultivar Severity

<chr> <int> <chr> <dbl>

1 control 97 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

2 control 104 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

3 control 111 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

4 control 118 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

5 control 125 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

6 control 132 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 0.00

7 control 139 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 2.34

8 control 146 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 7.56

9 control 154 TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat 28.78

10 control 97 CutterWheat 0.00

# ... with 44 more rowsVisualizing Data

> stop("

+ What visualization might be appropriate for these data?

+ What should be on the axes?

+ Should we use lines, points, bars, boxplots, etc?

+ ")Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos):

What visualization might be appropriate for these data?

What should be on the axes?

Should we use lines, points, bars, boxplots, etc?

If you haven’t taken the time to address the questions above, do so now.

What is ggplot2

The package ggplot2 is built off of the “grammar of graphics” in which visualizations are build layer by layer, starting with the coordinate plane and then adding geometric elements like lines, dots, bars, etc, and assigning metadata to values like color or shape.

The advantage of ggplot2 over R’s native plotting is that the plots are saved as R objects and can be modified by adding layers or even replacing data. This tutorial will begin to scratch the surface of how to use ggplot2, but to get a better idea of what is possible, you can browse the resources at http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/#learning-ggplot2 or examine the code of colleagues (e.g. Alejandro Rojas: https://github.com/alejorojas2/Rojas_Survey_Phytopath_2016).

It is important to note that, like everything else in the tidyverse, ggplot2 uses “bare” column names, meaning that you do not need to put quotation marks when specifying a column.

Creating our plot

Note: if you are reading this script after attending the workshop, the plot may look different due to the interactive nature of the workshop. This is indtended as an example.

Before we begin, we should become familiar with two functions:

ggplot()this function creates a ggplot object from a data set.aes()this function is a general way to specify what parts of the ggplot should be mapped to variables in your data.

Creating the base of the ggplot

To create our ggplot with nothing on it, we should specify two things:

- The data set (fungicide.tidy)

- The mapping of the x and y coordinates (from the data set, using aes)

> fungicide.plot <- ggplot(data = fungicide.tidy, mapping = aes(x = Julian.Date, y = Severity))If everything worked, you should see nothing. This is because ggplot2 returns an R object. This object contains the instructions for creating the visualization. When you print this object, the plot is created:

> fungicide.plot

Now you should see a plot with nothing on it where the x and y axes are labeled “Julian.Date” and “Severity”, respectively.

To break down what the above function did, it first took in the data set fungicide.tidy and then mapped the x and y aesthetics to the Julian.Date and Severity columns. Effectively, this told ggplot how big our canvas needs to be in order to display our data, but currently, it doesn’t know HOW we want to display our data; we need to give it a specific geometry.

Adding a geometry layer

All functions that add geometries to data start with geom_, so if we wanted the data to be displayed as a line showing the increase of severity over time, we would use geom_line(). If we wanted to show the data displayed as points, we can use geom_point(). We can also specify the color and shape of these geometries using aes().

To add a geometry or anything to a ggplot object, we can just use the + symbol. Here, we will add lines to the plot coloring them by Cultivar and differing the line type by Experiment

Note: From here on out, I will be wrapping all commands with parentheses. This allows the result of the assignment to be displayed automatically.

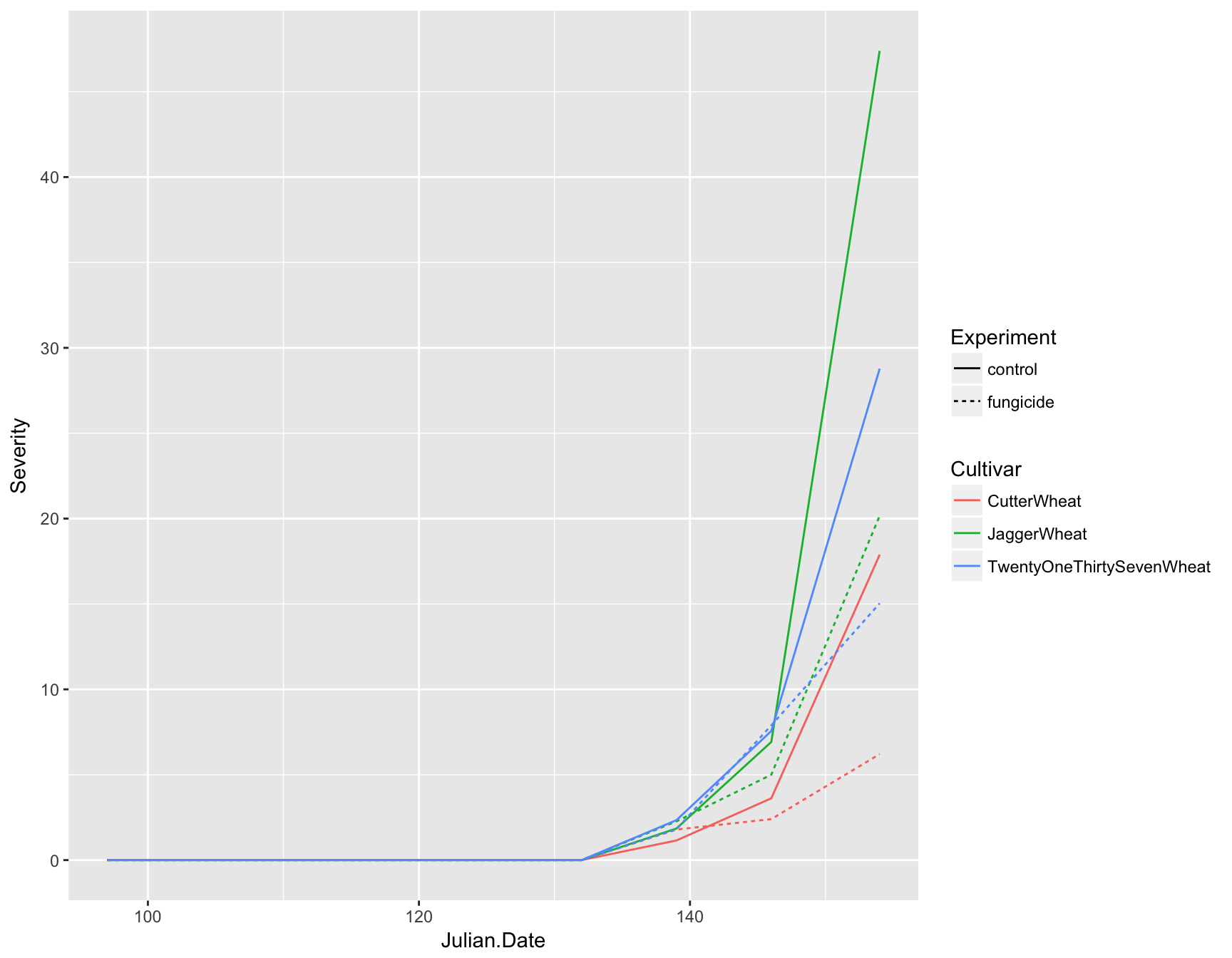

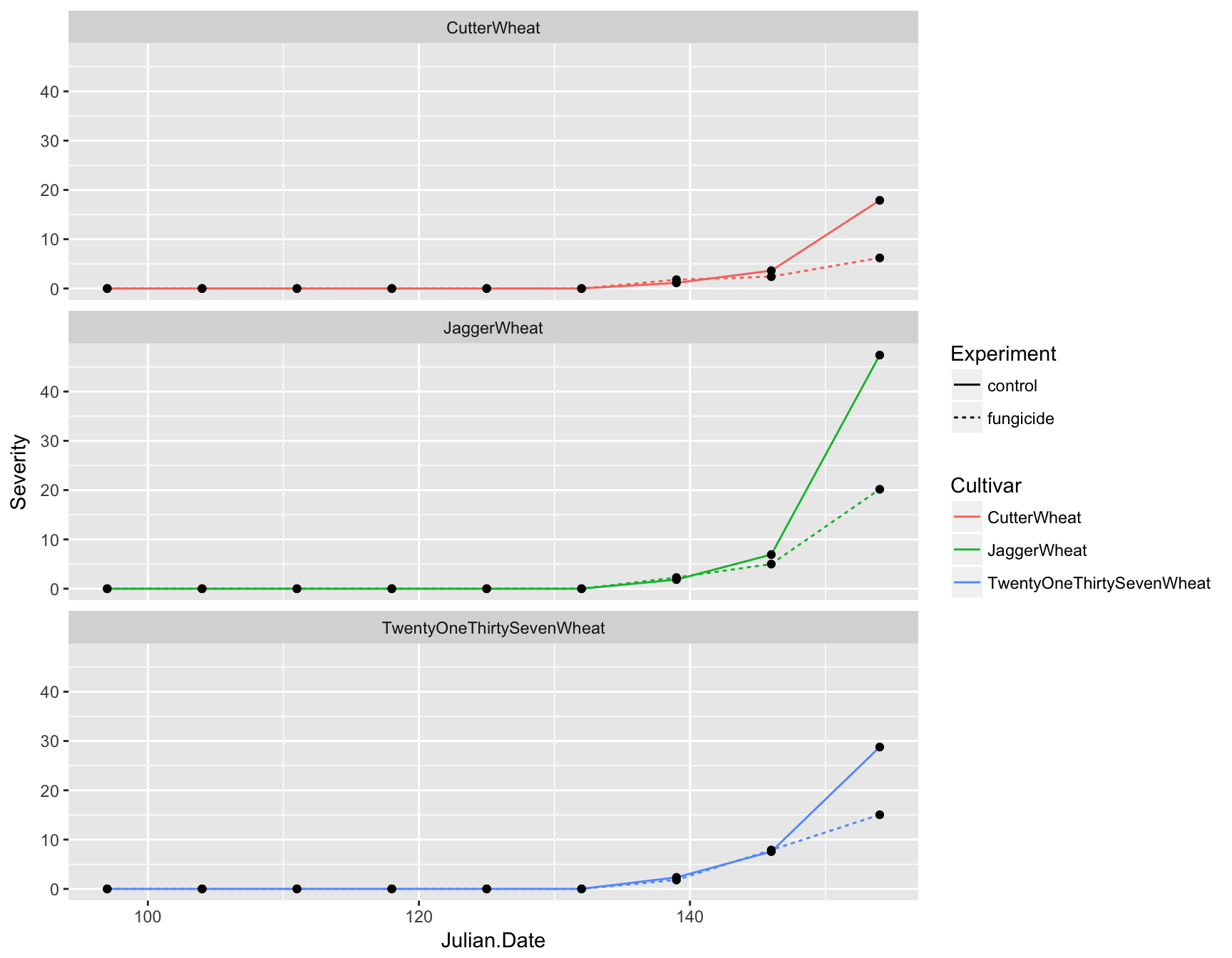

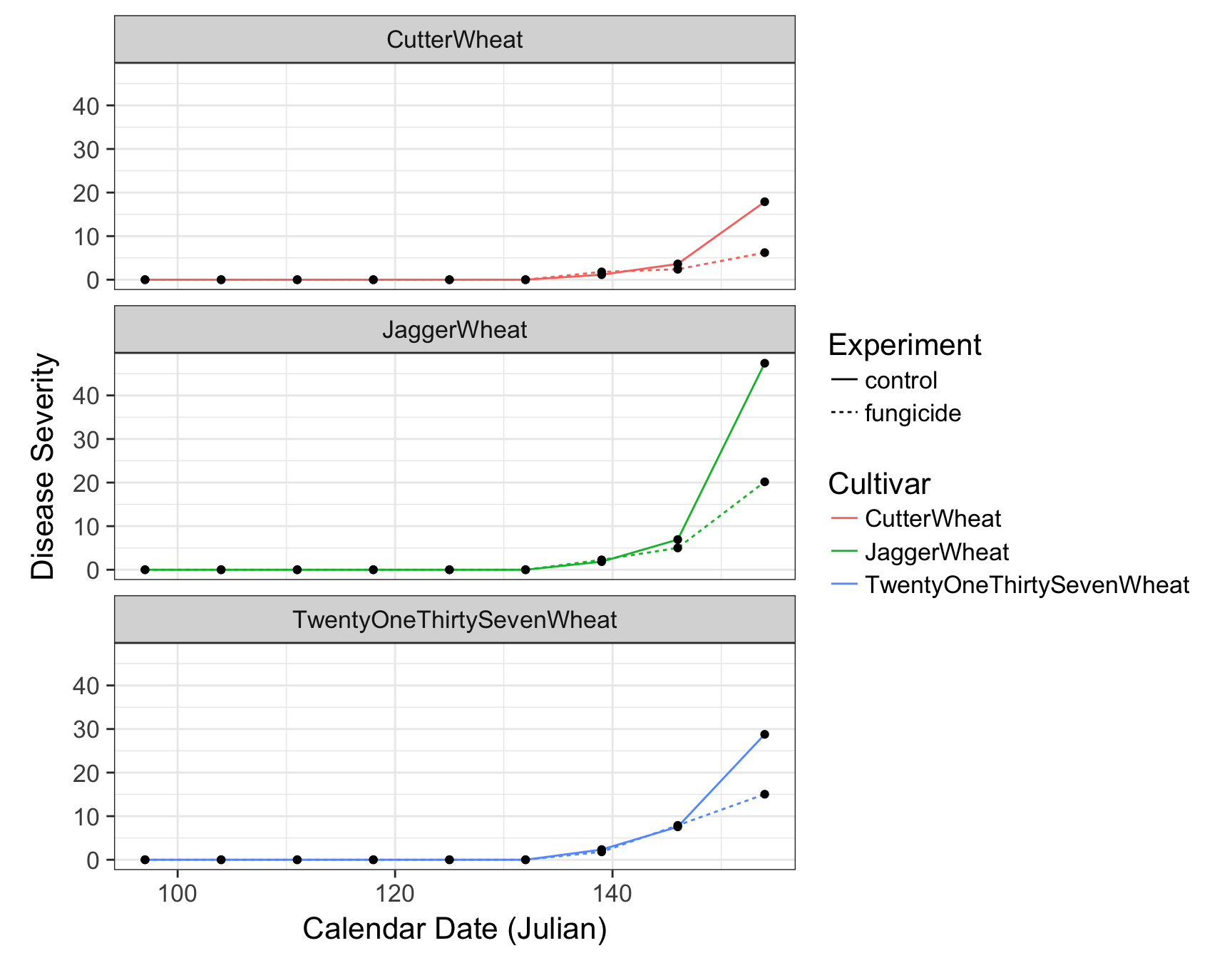

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + geom_line(mapping = aes(color = Cultivar, lty = Experiment)))

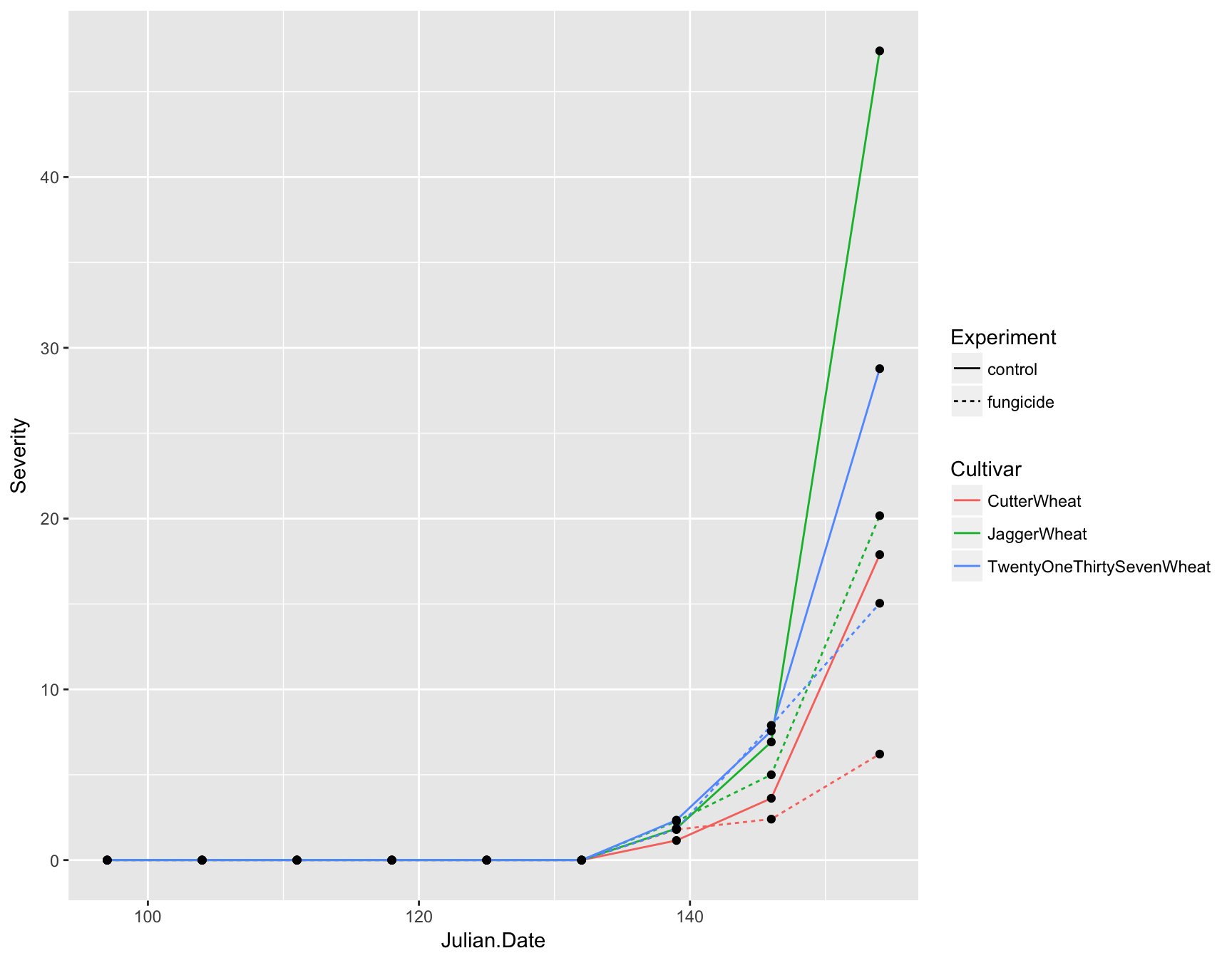

Now you can see that we not only have lines on our plot displaying the data, but we also have automatic legends. To highlight the time intervals, we can also add points to the plot by using geom_point(). Note that we don’t need to add any aesthetics to these since they are simply reenforcing the lines.

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + geom_point())

We now have a fully functional and informative plot using only three lines of code! Producing a visualization of your data can be an extremely useful tool for analysis because it can allow you to see if there are any strange patterns or spurious correlations in your variables.

Question

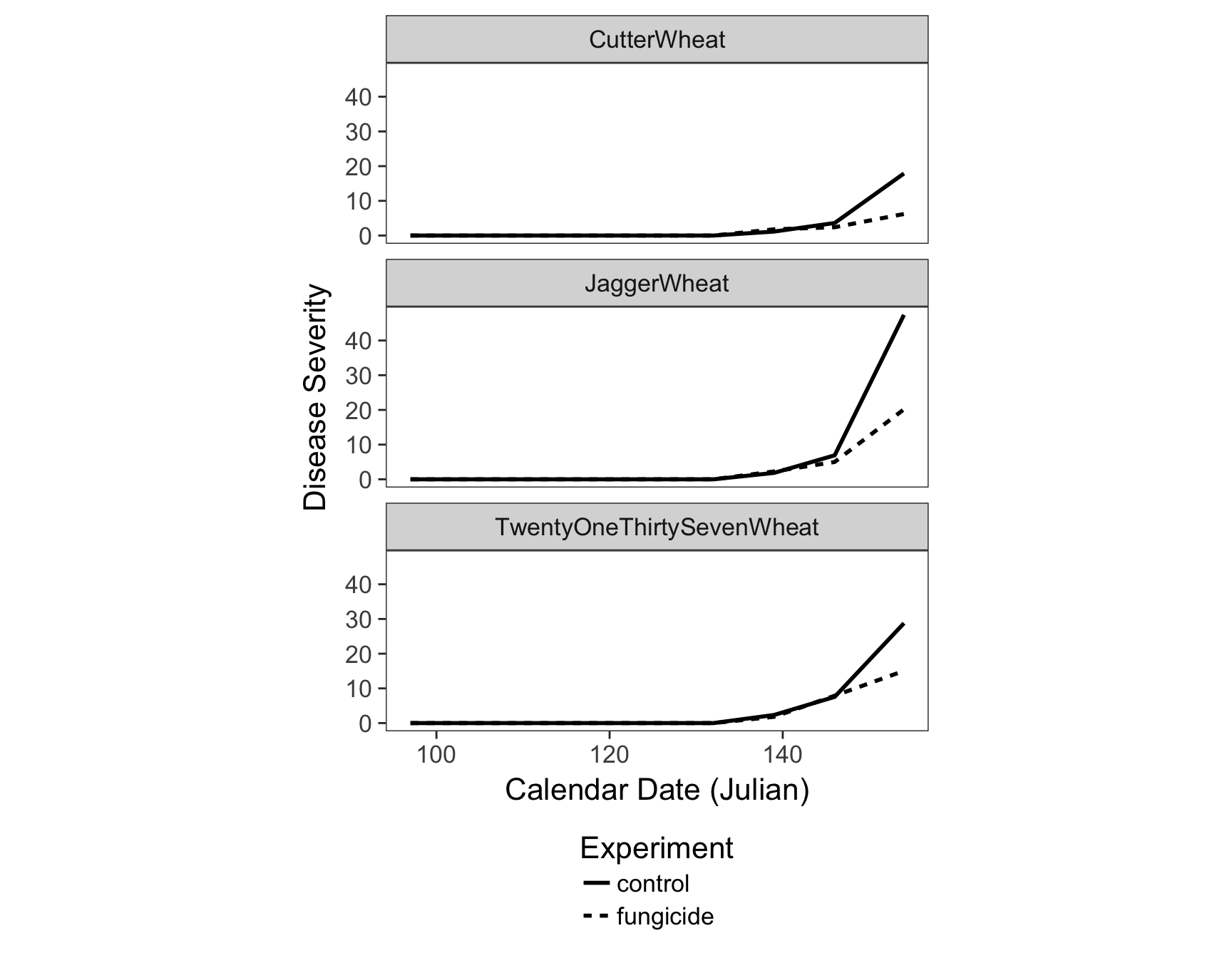

Now we can address the questions from Sparks et al. (2008):

- How does the size of the fungicide effect compare to the effect of resistance? Would it be the same as resistance?

- Since the fungicide typically is only active for two weeks after application, after looking at your graph, when do you think the fungicide was applied?

Of course, this plot is not quite publication ready. For one thing, it’s a bit too crowded and would cost a small fortune to include a color figure in a journal. We need to add some customization.

Preparing a publication-ready plot

In contrast to the above section, where layers are added to the plot, we are now manipulating the aesthetics of the plot in how the data and labels are displayed.

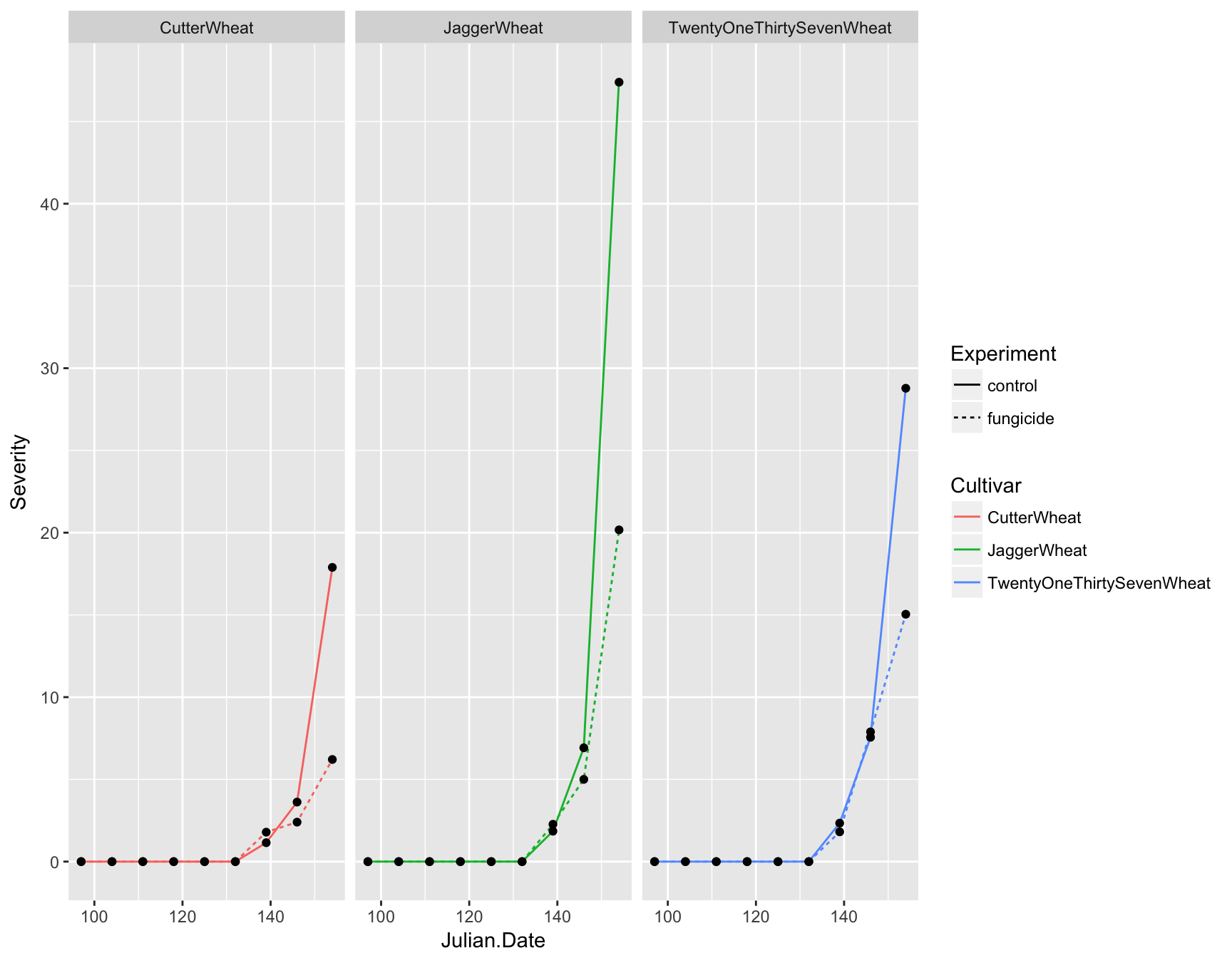

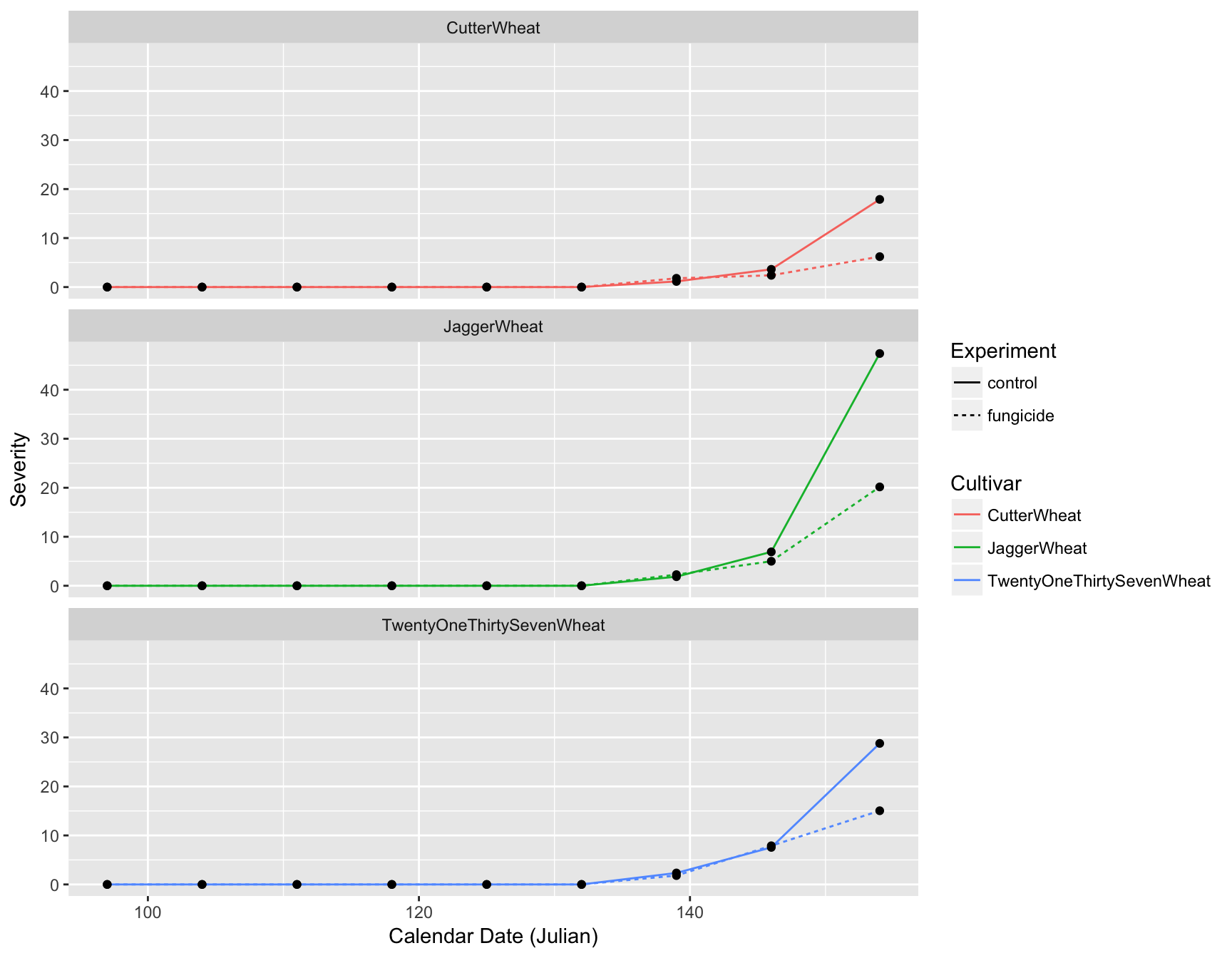

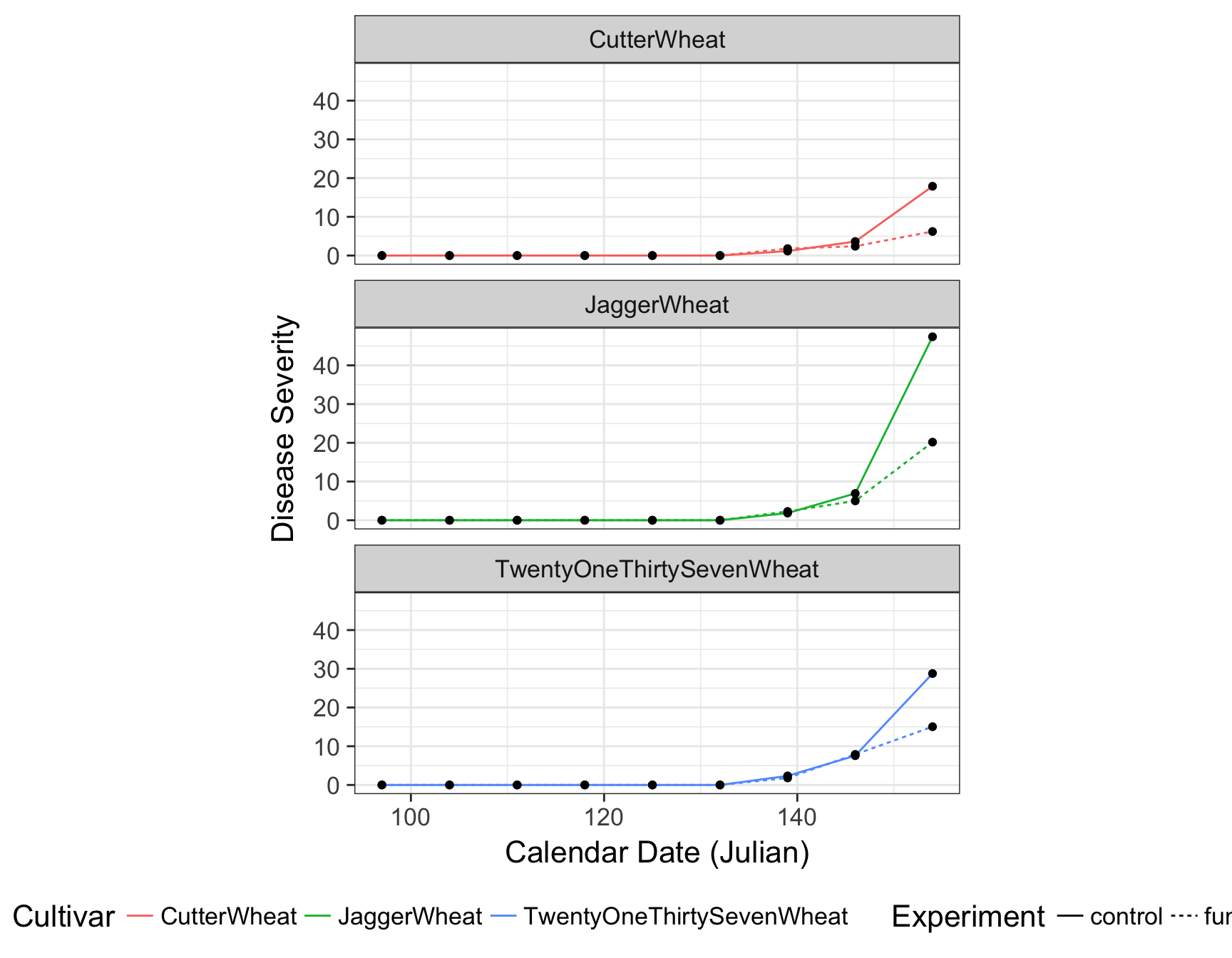

First let’s deal with the fact that this plot is over-crowded. We can separate our data into different “facets” based on a given variable. For example, we can create three plots separated by cultivar by using the facet_wrap() function and giving a formula (which contains a ~):

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + facet_wrap(~Cultivar))

This is much clearer, but instead of having three panels side by side, we want them in a column. We can specify the number of columns by using ncol. Again, because we are manipulating how the plot is displayed and not adding layers, we can simply re-call this function

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + facet_wrap(~Cultivar, ncol = 1))

Axis labels

We also need to update the axis labels. This is easily done with xlab() and ylab():

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + xlab("Calendar Date (Julian)"))

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + ylab("Disease Severity"))

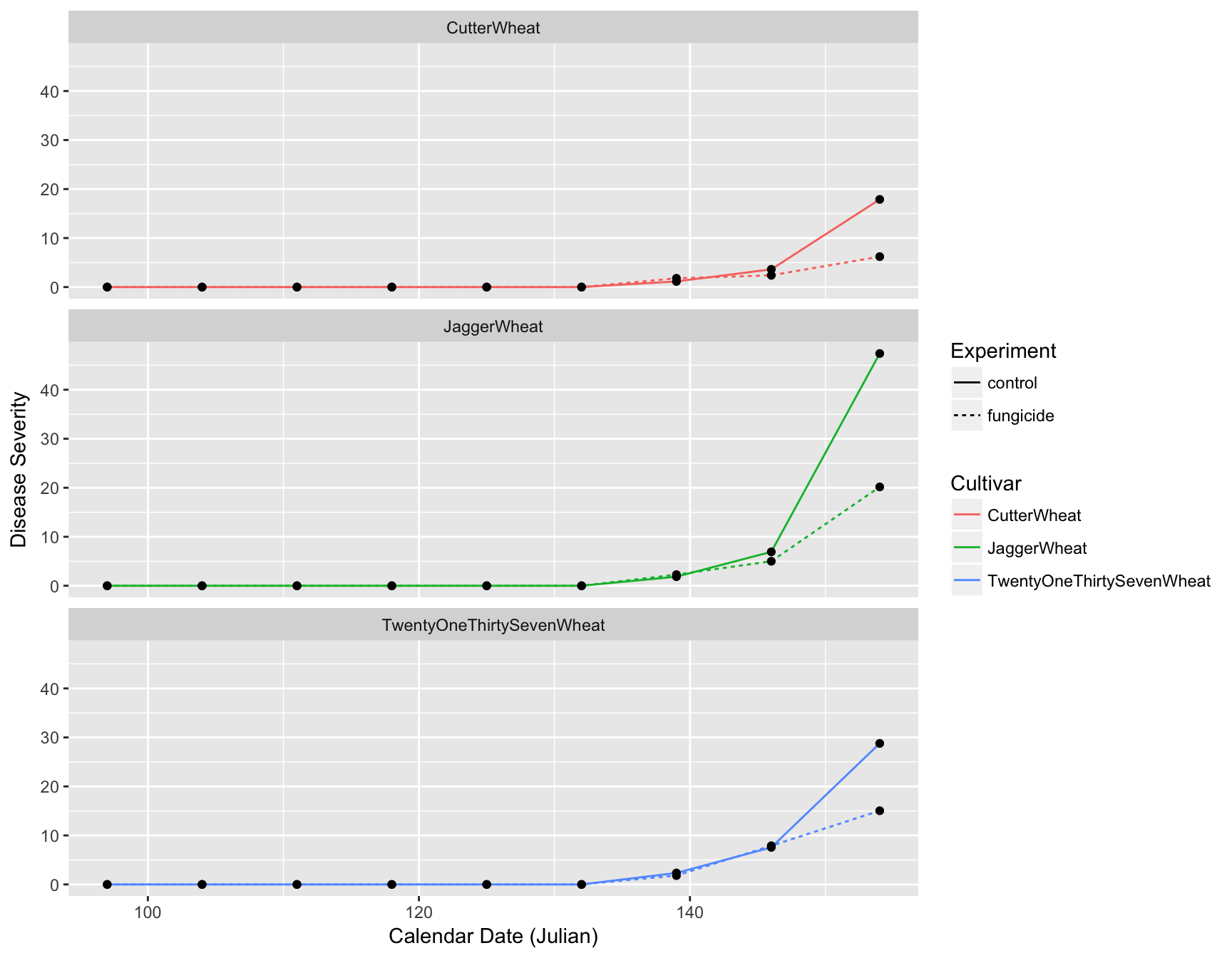

The labels are now okay, but it’s still not publication-ready. The font is too small, the background should have no gridlines and the axis text needs to be darker.

Adjusting Look and Feel (theme)

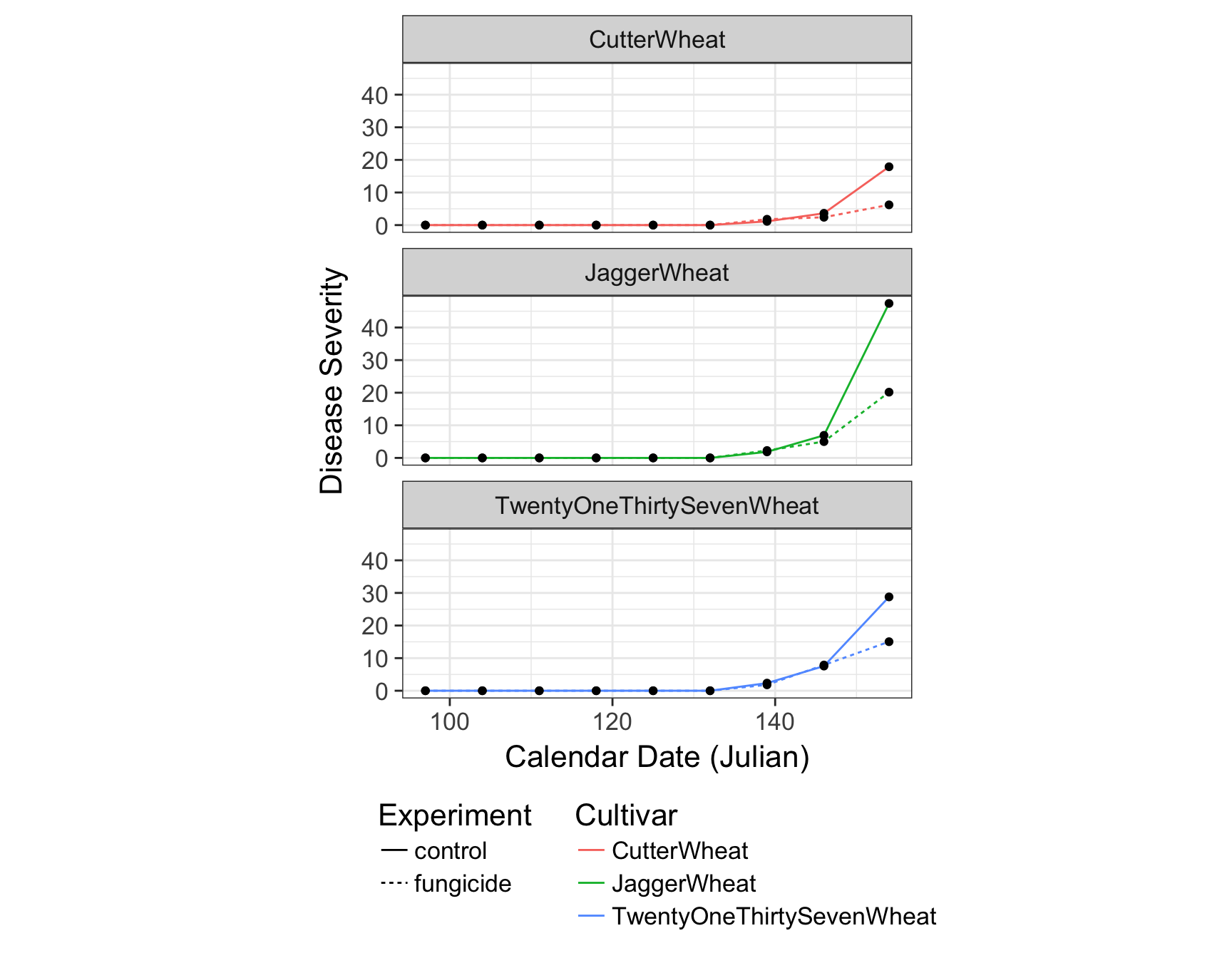

The first thing we can do is change the default theme from theme_grey() to theme_bw(). We will simultaneously set the base size of the font to be 16pt.

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + theme_bw(base_size = 16))

There are many different default themes available for ggplot2 objects that change many aspects of the look and feel. The ggthemes contains many popular themes such as fivethirtyeight and economist. Of course, as it is, the plot is still not ready for publication. For one, the legend is taking up to much horizontal realestate and the size of the plot is cutting off TwentyOneThirtySevenWheat.

To adjust granular aspects of the theme, we can use the theme() function, which contains a whopping 71 different options all related to the layout of the non-data aspects of the plot.

> stop("

+ Look at ?theme and figure out one of the following:

+ 1. change the aspect ratio of the panels

+ 2. remove the background grid in the panels

+ 3. change the placement of the legend

+ 4. change the orientation of the legend

+ ")Error in eval(expr, envir, enclos):

Look at ?theme and figure out one of the following:

1. change the aspect ratio of the panels

2. remove the background grid in the panels

3. change the placement of the legend

4. change the orientation of the legend

When we inspect the help page of the theme() function, we can find out how to adjust several parameters to make out plot look acceptable:

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + theme(aspect.ratio = 1/3))

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + theme(legend.position = "bottom"))

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + theme(legend.direction = "vertical"))

> (fungicide.plot <- fungicide.plot + theme(panel.grid = element_blank()))

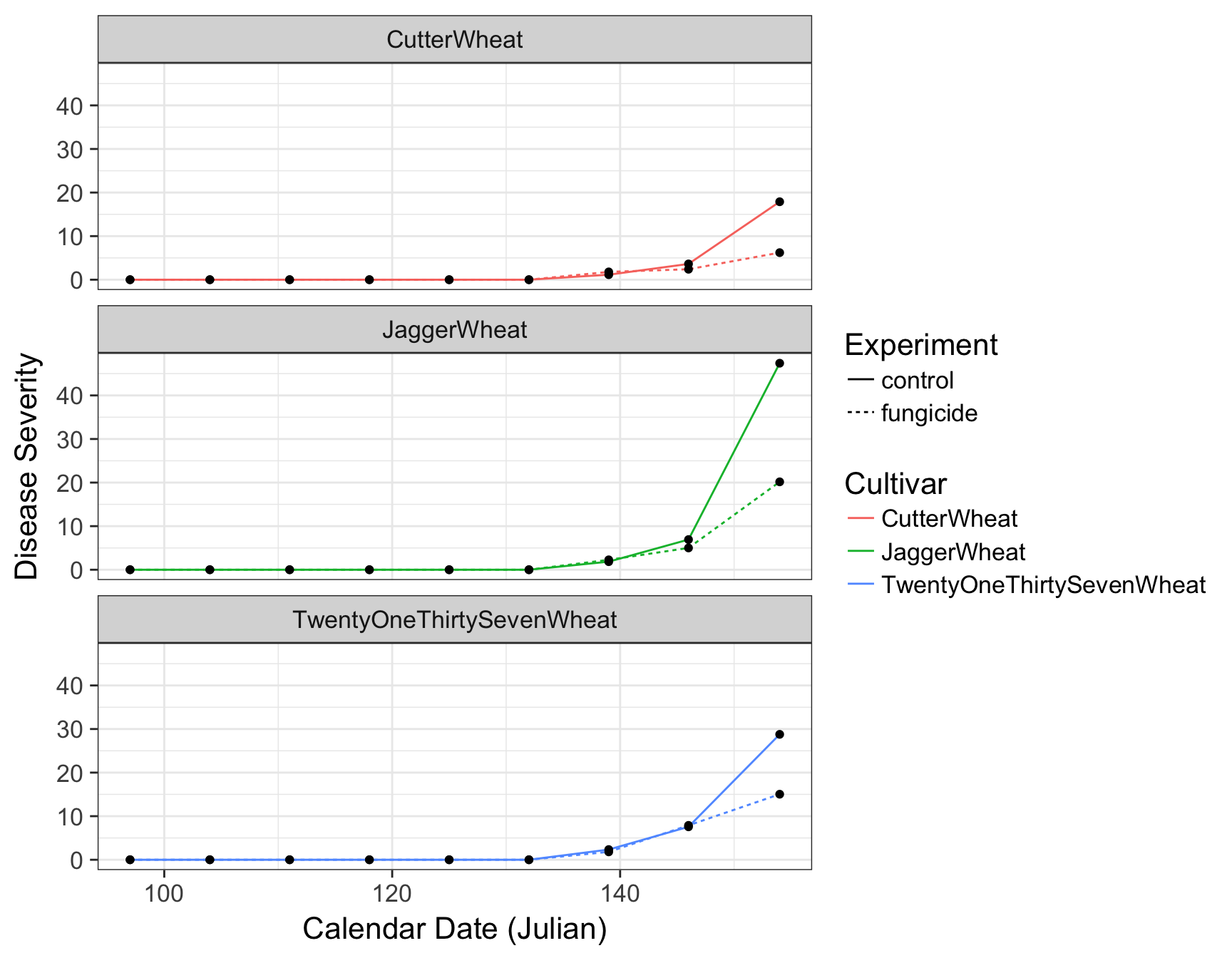

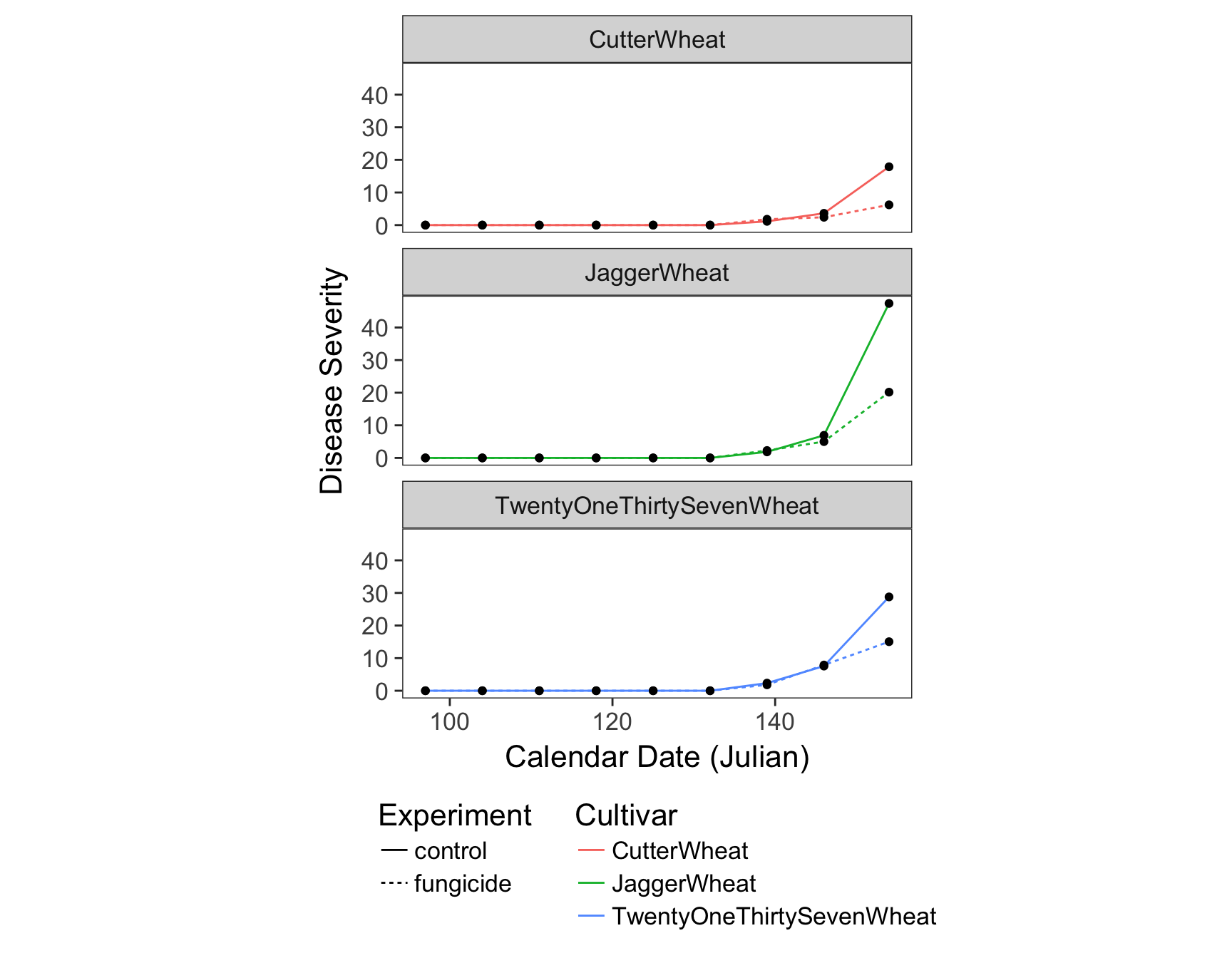

Putting it all together

Because we can add information to a plot with the + symbol, we can add all of the elements in one go. Let’s combine what we have above, but removing the points and the color of the lines since these are redundant.

> fungicide.plot <- ggplot(fungicide.tidy, aes(x = Julian.Date, y = Severity)) +

+ geom_line(aes(lty = Experiment), size = 1) +

+ facet_wrap(~Cultivar, ncol = 1) +

+ theme_bw(base_size = 16) +

+ theme(aspect.ratio = 1/3) +

+ theme(legend.position = "bottom") +

+ theme(legend.direction = "vertical") +

+ theme(panel.grid = element_blank()) +

+ xlab("Calendar Date (Julian)") +

+ ylab("Disease Severity")

> fungicide.plot

Saving your plot

Now that we have our plot finished, we can save it with the ggsave() function, which allows us to save it as a pdf, png, svg, eps, etc. file.

> ggsave(filename = "results/figure1.pdf", width = 88, units = "mm")Saving 88 x 178 mm image

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.